Cape Read online

For Mom and Dad, my first superheroes

Two

WHEN THE WORLD NEEDS A hero, sometimes you have to become one.

That was my mom’s thinking. And it seemed simple enough that even knuckleheads like my brothers, Vinnie and Baby Lou, could understand. Because Mam did that kind of thing all the time. Like when she made corned beef sandwiches for the family next door when she saw they couldn’t pay for groceries, or gave away one of her best dresses to the neighbor whose husband died fighting the Nazis—so the lady would have something decent to wear to his funeral.

For my little family, the whole world was basically our third-floor apartment. The one above Mr. Hunter’s barbershop on Captain Flexor Street in West Philadelphia, between the cleaners and the weeping willow tree. And as Mam liked to say, I was the hero of it.

That’s because my taking a job at Gerda’s Diner down the block helped pay the rent each month, which kept us from getting kicked out onto the street.

Which made my little brother Vinnie stop tugging on that clump of hair above his forehead and worrying all the time.

Which made my mom able to breathe.

But let’s be honest here. Clearing the diner’s tables of lipstick-smudged coffee cups and dirty plates stuck with scrambled eggs? That didn’t feel too heroic to me.

It wasn’t anything like the superheroes from years past—the ones who soared over rooftops and battled villains to save our city. Using superstrength to stop a speeding train from crashing off a bridge? Protecting a bunch of innocent people from harm? Now, those were things heroes did. And people loved them so much for it, they named schools and parks and streets after them.

Nobody’s naming anything after me.

Lately I’ve started wondering where all the superheroes have gone. Because with the war on, we sure could use a few of them flying around, all billowy capes and mysterious masks over their eyes and shiny boots. The papers and radio reports haven’t had much news about superheroes, not since the war’s fighting turned really bad.

Some people even stopped believing in them. Superheroes were becoming just bedtime stories parents told their kids, like tales of King Arthur or leprechauns or the tooth fairy. Others started thinking they were just made-up characters in comic books—not real people trying to do good.

I couldn’t bear the thought. I told myself all the superheroes were off in the Pacific Ocean fighting the Japanese alongside our troops there. And over in Europe battling back against Germany’s Nazis. But to be perfectly honest, part of me was starting to worry they’d hung up their capes and decided to wait for better times.

This was the argument Emmett and I were having last night at my kitchen table over plates of Spam hash. We were supposed to be doing homework, but we kept getting distracted.

“Face it, Josie,” he was saying. “The caped heroes of your beloved comic books are history. Done, finished, behind us. If you keep going on about them, people are going to think you’re crazy.”

“I’m not crazy, Emmett Shea, and you know it.” My voice cut through the usual noise in our apartment—over the radio, my brothers’ Parcheesi game, my cousin’s sewing machine, and my mother’s teakettle. “Superheroes are still out there saving people’s lives and rescuing dogs and stopping evildoers. They’re just quiet, for some reason. It’s probably the war. Or the heat this summer . . .”

Emmett gave me a doubtful look. He didn’t even need to say what he was thinking. That’s because we both knew that superheroes had been quiet for longer than just the past couple of weeks, when the weather had started heating up. More like the past couple of years. When I really thought about it, superheroes hadn’t been spotted in Philadelphia since I was in fourth or fifth grade.

“Hurry up and guess, Emmett,” I groused, pointing at his pencil. I wasn’t annoyed with the time Emmett was taking to solve my puzzle. It was his attitude about superheroes that bothered me. “You’ve stared at those clues long enough.”

“Don’t rush me, Josie,” he said, unfazed by my crankiness. Nothing could ruffle Emmett’s feathers. Especially when he was puzzling. “And don’t be salty with me over superheroes quitting. Hauntima, Hopscotch, Nova the Sunchaser—even that favorite pair of yours, those sisters Zenobia and the Palomino. They must figure there’s a whole bunch of puzzle solvers and other smarties like you and me coming to take their jobs. So they quit.”

He gave me a smirk, then stared harder at the clues I’d laid out for him.

175, 21, 5–6

7, 5, 8

34, 12, 1

306, 21, 5

287, 4, 4

“I don’t think it’s an alphabet cipher, since some of these numbers are higher than twenty-six,” Emmett mumbled, thinking out loud. “So maybe a book cipher?”

I dropped my pencil onto the paper and groaned. He was almost too good at this! I’d have to read up on harder puzzles so I could really stump him next time.

“Hmmm. What book would you choose?” His eyes scanned the kitchen shelves, searching the spines of Mam’s cookbooks. I kept my eyes on my homework sheet, trying not to give myself away. Because in the doorway to the dining room, just beside the radio, sat a stack of my favorite books.

“Aha!” Emmett shouted, pouncing on them. “It’s got to be one of these.”

He scooped up the stack and plunked it down on the table, jolting our pencils and papers. Then he arranged my books in a row, side by side, so he could read each title plainly.

“No fair, Josie. Book ciphers are only good when we have the exact same book. That way we each can look up the pages.”

I shrugged and gave him a look, trying hard not to let him catch me smiling.

“If you can’t figure it out, Emmett, don’t start whining. A puzzle’s a puzzle. Maybe mine are just too hard for you. . . .”

That did the trick.

“Nobody is saying your puzzles are too hard, Josie. Now, let’s see—what would you choose for your book cipher? Mr. Popper’s Penguins? Little House on the Prairie? The Boxcar Children?”

I tapped my pencil on my teacup and pretended not to hear him. He’d have to figure this out on his own. No hints from me.

“Come on, Josie, help me! Just a teeny-tiny clue.”

I pointed at the rows of numbers and reminded him that I’d given him five clues already. But Emmett was desperate.

“I’ve got to be home before my mom gets off her shift. So give a guy a break, Josie. Which book did you choose? I can solve it from there.”

I tapped my temple and teased Emmett just a little bit more.

“Think about it,” I began, pretending exasperation. “One of these books has the greatest redhead of all time! In all of literature! How can you ask me, of all people, which book I’d pick?”

Emmett stared at my raging-red curls, and now it was his turn for exasperation.

“Anne of Green Gables!” he hollered, slapping his hand onto the cover of the last book and whipping it open. “I should have known you’d choose this one. But it’s a little predictable, Josie, when you think about it.”

“Well, clearly you didn’t think about it, now, did you?”

Turning the pages, counting down the lines, then over the right number of words, Emmett solved my cipher in a matter of seconds.

“Okay, the first clue is on page 175,” he mumbled, double-checking himself, “twenty-first line, the fifth and sixth words. ‘Second shelf.’ ”

“And the whole puzzle reads?”

Emmett cleared his throat and tried to sound like a master puzzler.

“Your cipher, Miss Know-It-All Josephine O’Malley, reads: ‘Second shelf behind you red box.’ ”

He waited just a beat or two, staring at me. Then the meaning sank in. And Emmett jumped to his feet, raced to the second shelf of

the pantry just behind his chair, and grabbed the red tin cookie box with the Lorna Doone label. I’d just refilled it that afternoon.

“Shortbread cookies! My favorite!”

“Zenobia could have solved that faster,” I pointed out. “Or the Palomino, Hauntima, Hopscotch, Nova the Sunchaser . . .”

Three

EMMETT HAD MADE IT CLEAR last night over homework and puzzling that he didn’t believe there were superheroes around anymore. But I sure did. That’s because I needed them—a lot. So as I stood there in front of Gerda’s Diner, my cheeks burned hot, and my hands shook with anger. Toby’s team of bullies couldn’t even ride the bikes they’d stolen from my little brothers—their legs were too long. They’d probably just give them to the youngest of their lunkhead gang, Toby’s bullies-in-training.

Toby must have seen my outrage, because he took off running just as I lunged for him. Toby was bigger than me but clumsy. So when I whipped my broom out ahead of me and caught his feet, I sent him spilling onto the sidewalk.

The anger inside me made me want to pounce, claws bared. Instead, as he rolled over to face me, I pressed the handle of the broom to his chest, in the little round spot just between his collarbones. He gasped, but I’d caught his attention.

“I’ve had it with you, Toby,” I said, my voice tight, my heart pounding in my chest. “Why can’t you leave us alone?”

Toby’s taunting had been easy enough to ignore at first. Mam was always reminding us not to pay any mind to the unkind things people sometimes said. Cruelty comes from weakness, she’d tell me and my brothers. People who feel weak want to find somebody to look down on. But they’re already in the mud and the muck—don’t let them pull you down with them.

Hands shaking, I gripped the broomstick tighter and stared down at Toby’s arrogant smirk. Weakness? Who did Mam think felt weak? Toby? Leader of our neighborhood bullies? The kid with the bossy dad who seemed to run our whole block?

Toby and his beady-eyed buddies liked to tease me on the monkey bars at recess, whenever they caught me singing songs from back home in Ireland. Speak American! they’d shout. Or go back to where you came from.

“I’m warning you, Josie O’Malley,” Toby growled now, wrapping his hands around the broomstick and trying to push me back. “My dad won’t like hearing about this.”

“He’ll tell on you, Josie,” said Vinnie, his words high-pitched and panicky. “It’s not worth it!”

“Mam won’t like it one bit,” added Baby Lou. I could tell he was near tears, though he’d never let Toby Hunter see him cry.

Mam.

I squeezed my eyes shut and tried to bottle up my rage.

Mam couldn’t take one more thing.

Toby’s loudmouthed father ran the barbershop downstairs, and he owned our whole building. If Toby told his dad on me—conveniently leaving out the parts about stealing my brothers’ bikes and lunches, and their confidence, too—Mr. Hunter would never listen to my side of things. He’d kick my family out of the apartment. And that would be too much for my mom to take.

Especially now, since the news about Dad.

“Be safe,” she’d told me this morning, her words part whispered prayer, part command. “Mind yourself, Josie. I can’t bear anything happening to you or the boys. Or to Kay. I can’t lose you.”

Be safe. No trouble. Come straight home. Mam needed us to live like mice, scurrying here and there without drawing attention to ourselves. And I had promised her that’s what I’d do—so help me, Toby Hunter.

I would not steal his bike right back, just to make things even.

I would not tell on him to the cops or to my teachers.

I would not punch his splotchy pink face, even though I wanted to so badly, it made my palms itch.

But the puzzler tryout? Now, that’s something I wasn’t about to give up. Even though my mom wanted us staying inside the apartment and practically wrapping ourselves in pillows, I refused to walk away from this chance. Math games, word games, solving ciphers—all these things came easy to me.

Getting this puzzler job would be my own way of fighting the war, small as it seemed. For Dad, who’d been fighting since the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. For Mam, who worked a second job putting battleships together at the shipyard. For my little brothers and Cousin Kay.

I was willing to walk away from battles with Toby, like Mam wanted. But not the war.

I lifted the broomstick and stepped aside.

“Off to school now,” I snapped to Vinnie and Baby Lou. I could hardly look at them. The mixture of shame and embarrassment made the broom weigh heavy, like it was made of iron instead of wood. My arms sagged. “You’ve got to run or you’ll be late. Go!”

For once in their lives, my knucklehead little brothers did what I asked of them.

Choking and sputtering, Toby got to his feet.

“Smart move for such a stupid girl. I’d hate to have to tell my dad we’re renting to a bully.”

And he let out a laugh, a deep and dangerous guffaw that hit me like a fist to my stomach. It lingered menacingly behind him as he swaggered off after his thieving buddies.

I turned back toward the diner, past the wirehaired dog barking on his leash, and glanced up at the well-dressed owner holding the newspaper. She was looking at me now, reading my face like it was one of those news stories. I wondered what she’d caught of the fight between Toby and me.

Stupid. Is there a more hurtful word in the English language?

I glanced up and saw my reflection in the diner window: curly hair corkscrewing in every direction, faded dungarees needing a wash, loose white blouse making me look scrawnier than I already was.

Stupid girl.

Was I foolish to try out for the puzzler job? Was it ridiculous to think I was a math whiz like my cousin Kay? I swallowed hard, trying to push the doubts away. But maybe Toby Hunter was right. Maybe I was just a stupid girl.

And what good was a stupid girl to anybody? Especially one who couldn’t even save a couple of red bikes.

“Hey, Josie!”

The shout came from the other side of the dog and his owner. It was Emmett. He was a little breathless as he trotted over, his usual cheerful smile replaced by a scowl.

“That Toby Hunter.” He shook his head, and his eyebrows formed a deep V. Clearly he’d run into my brothers on their way to school. “He’s had a grudge against you ever since that math contest last year. You made him look bad. Scratch that—he made himself look bad, since he’s nothing but oatmeal up there.” And he knocked his knuckles on his forehead.

I shrugged and stared down at the sidewalk, kicking at a bottle cap. What was I supposed to do against a grudge? People made no sense to me sometimes. Maybe that’s why I liked puzzles and math so much—they were things I could figure out.

And they never made me feel like I did right now. Stupid.

“I can’t do anything to stop him,” I said, fighting the urge to snap my broomstick. “Punks like Toby can do whatever they want. And people like me just have to live with it.”

“Don’t underestimate yourself, Josie,” Emmett said. “You may feel like you’re powerless right now. But things can change.”

I looked away, suddenly wanting to hide behind my broom.

“Listen, about your brothers’ bikes,” Emmett went on. “I’ll try to help you get them back. But don’t do it alone, Josie. Toby can make things really bad for you.”

I nodded. I really did need somebody like Emmett on my side—brains as well as kindness. A little like Zenobia, my all-time favorite of the superheroes. I put my hand on my comic book in my back pocket. Zenobia’s powers, like heat beams and levitation and superstrength, were amazing, but what I liked best about her was that she used her superpowers to help people. And not just here in Philadelphia but around the country too.

That is, before she and the other superheroes stopped showing up.

“He meets Mat?” I asked Emmett, feeling a little better about things.

/> “You know it,” he answered, a grin breaking out on his goofy face. And then he threw an easy punch at my shoulder. “I help lonesome Jay?”

A laugh pawed at my stomach like a playful puppy. That’s because Emmett and I were using our secret codes. He meets Mat was Emmett’s name—Emmett Shea—with the letters scrambled up like a plate of diner eggs. And I help lonesome Jay was mine—Josephine O’Malley.

Emmett and I had started rearranging the letters in names and places to pass time during our boring classes last year. We liked to slip each other notes in our secret jumbled language so nobody knew what we were talking about.

Solving each other’s puzzles was just for laughs at first. But as the school year wore on and things got harder for both of us, we came to depend on our notes back and forth. And when nothing else made sense—not our parents, our friends, or this terrible war—we both knew we could count on each other to help unscramble things.

“Thanks,” I called after Emmett as he hurried off. “I needed that!” He waved and shouted something about catching up with me later over milkshakes. I watched as the stream of people passing on the sidewalk swept him up, his brown head bobbing along with the others on their morning commute.

But as I waved after him, I noticed Emmett wasn’t headed toward our school. He was trudging off in the opposite direction. And it suddenly occurred to me that Emmett Shea must be up to something, but he hadn’t let me in on his secret.

Four

WHY THE SCOWL, JOSIE?”

The door to the diner opened, and Harry Sawyer, who helped Gerda run things, nodded for me to come back inside. My frustration with Toby must have shown on my face.

“I’ve never heard you say a bad word to anyone,” he said, reaching a hand up to quiet the tinkling bell that hung above the door. “What’s put a flea in your ear?”

“Meanies,” I said, using one of Baby Lou’s words. “Bullies, brutes, tough guys, lunkheads. Whatever you want to call them.”

Harry let out a sigh and took the broom from my hand. “Well, from what I saw, you were a bit unkind yourself.”

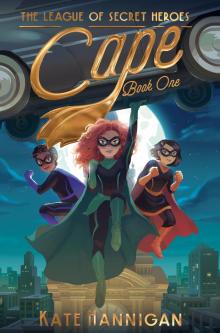

Cape

Cape